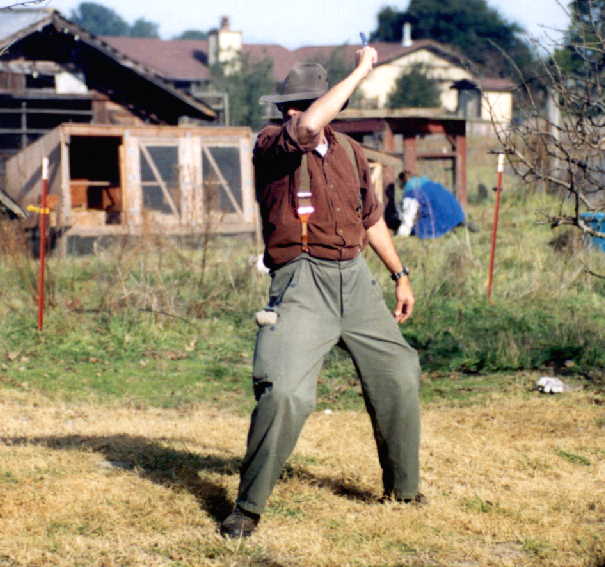

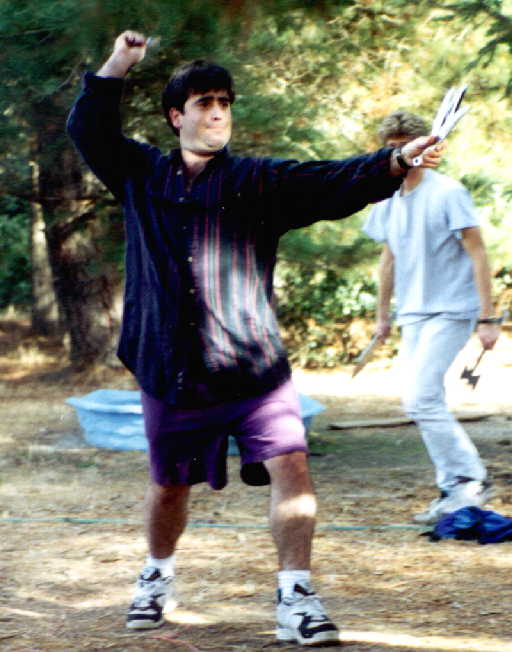

Stance,

grip, throw, and of course, the size,

weight, and shape of

the knife itself, all have an effect on the flight of the knife,

including its spin rate relative to its forward motion. The behavior

of the knife is predictable to the extent that the thrower can

control all of these factors. You have to start somewhere. Choose a

stance,

grip, throw, knife, etc., and try to

repeat what you do

again and again once you have found a distance that works for a half

turn, usually the easiest, unless the knife's balance favors a full

turn (blade heavy).

grip, throw, knife, etc., and try to

repeat what you do

again and again once you have found a distance that works for a half

turn, usually the easiest, unless the knife's balance favors a full

turn (blade heavy).

Sometimes it helps to throw very hard because it is one degree of force you can repeat oven and over, until your arm tires. It is important, in this case, to choose the right knife because if it is too light it can hurt your arm to throw really hard. As you get better, you become stronger and able to produce a consistent snap without throwing full-force. You may then begin to deliberately vary some of the influential factors, and experiment with their effects.

Ed Sackett has written us a nice essay on the HOW of knife throwing. The main comment I have about Ed's article here has to do with his distance calculations. I find that there is considerable variation from person to person in the distance at which a given throw will make a knife stick. The stance, grip, and throw that work for one person at 13 feet may work for another at 11! You have to find the distances at which your baseline works for you.

Once you have accounted for individual variations in the basic one half or one turn distance, there is the matter of holdover. Holdover is familiar to shooters of all kinds, not to mention people who throw lots of rocks or baseballs. Gravity begins to affect a projectile the moment it is released. That means you can never shoot or throw straight at your target, but always a little above it. The further from your target you get, the more pronounced the holdover becomes because the pull of gravity is constant for every millisecond the projectile is in flight. This means that a knife travels a little farther to the target than one would think. A knife released 10 feet from its target might travel 10.5 feet to get there. At 20 feet, the knife must travel an arc of not 21 feet, but perhaps as much as 23, because the effect of gravity is cumulative. Thus the two turn distance is considerably smaller than twice the one turn distance, because you have to account for the distance added by the holdover even after you have accounted for the length of your arm as discussed in Ed's article.

We also have a HOW TO essay by Harald Moeller, creator of the Viper throwing knife, one of the more elaborate (and expensive) entries in the equipment kit available to knife throwers. My issue with Harald (same caveats apply where his discussion of distances is concerned) is his prejudice against throws from the blade. Harald is quite right where double edged knives are concerned. When one grips them by the blade, one wants to release with the flat-of-the-blade parallel to the ground. This is OK for a half turn, but becomes a disproportionate handicap as distances increase.

A single edged knife can be gripped

from the spine with the thumb on one side and the fingers curled on

the other. This permits an edge-on throw if the thrower rotates

the wrist a quarter turn, but this isn't a natural throwing

position for most people. Most professional throwing knives, however,

have no edge at all (just a bevel) and so may be gripped by the

blade, exactly as they are by the handle, eliminating the blade-hold

disadvantage.

A single edged knife can be gripped

from the spine with the thumb on one side and the fingers curled on

the other. This permits an edge-on throw if the thrower rotates

the wrist a quarter turn, but this isn't a natural throwing

position for most people. Most professional throwing knives, however,

have no edge at all (just a bevel) and so may be gripped by the

blade, exactly as they are by the handle, eliminating the blade-hold

disadvantage.

Bob Karp taught me to cover edges (up to about 1/2 inch from the tip) with a layer or two of electrical tape permitting one to grip such a knife as you would an edgeless thrower. Harald's very well balanced (but double edged) knives throw beautifully from the blade this way.

Have fun all!